The Road to Equality After the War: AAPIs in the Civil War

On the road to civil rights for Asians and Pacific Islanders in the United States, the challenges faced connect to the Civil War and the promise of equality that was not easily granted to future generations.

This blog is a continuation of Those Who Served, a blog written in celebration of AANHPI Heritage Month and Civil War history. All information can be sourced from Asians and Pacific Islanders and the Civil War, a well-researched text on the subject edited by Carol A. Shively. We encourage readers to explore more from the experts who contributed invaluable research with the goal of making this largely unknown history visible.

The story of Asian Americans in the Civil War cannot be shared without the story of civil rights for Asian Americans. These events of exclusion and discrimination resulted in the wake of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which came right after the Civil War, denying AAPIs rights to citizenship. In many cases, full participation in education and democracy were threatened.

In these events of seeking justice and equality, Asians and Pacific Islanders looked to the 14th and 15th Amendments: the laws of the land that were made possible in the wake of the Civil War. These are some stories of AAPIs combating injustice, some successfully and some unsuccessfully, that can be connected to the Civil War:

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882

The first immigration law to probit immigration on basis of race or national origin, banning all immigration from China. Under Exclusion, processing of citizenship essentially meant denial. The law’s processing was lengthy, and immigration inspection stations became detention centers in which those seeking entry were commonly locked in for days, weeks and months. Sometimes, even American-born Asians would wind up being deported instead of allowed to land if they were unable to provide acceptable documentation.

Tape v. Hurley (1885)

Just two years after the Exclusion Act, Mamie Tape, an 8-year-old Chinese American girl and a U.S. citizen born to two Chinese immigrants, was denied entry to a California Spring Valley public school in 1884. When she and her parents challenged this exclusion, they cited the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment that granted citizenship to formerly enslaved African Americans. “To deny a child, born of Chinese parents in this State, entrance to the public schools,” the court reasoned, is “a violation of the law of the state and the Constitution of the United States.”1

Though the Tapes initially succeeded, California would go on to pass a law calling for segregated schools, arguing that would satisfy the need for “equal protection.” Despite mother Mary Tape’s letter to the board of education that her demand for equality was “more American” than the “race prejudice” of school segregation, this would not be overturned until 1954. This was an example of students of color being considered “separate but equal,” even before Plessy v. Ferguson.

United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1895)

In this case, Wong Kim Ark, an American citizen by birth, was refused entry into the United States. This was on the grounds that because he was born to “aliens ineligible to citizenship,” 2 he was not a citizen, subject to the Chinese Exclusion Act and the 1790 Naturalization Act. U.S. citizenship was a basic right denied all Asian immigrants by the Naturalization Act, which restricted naturalization to “free white persons.”

He appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1898, and his citizenship was upheld together with “all persons” 3 born in the U.S. This is a crucial example of how the 14th Amendment could protect such rights through its provision of equality.

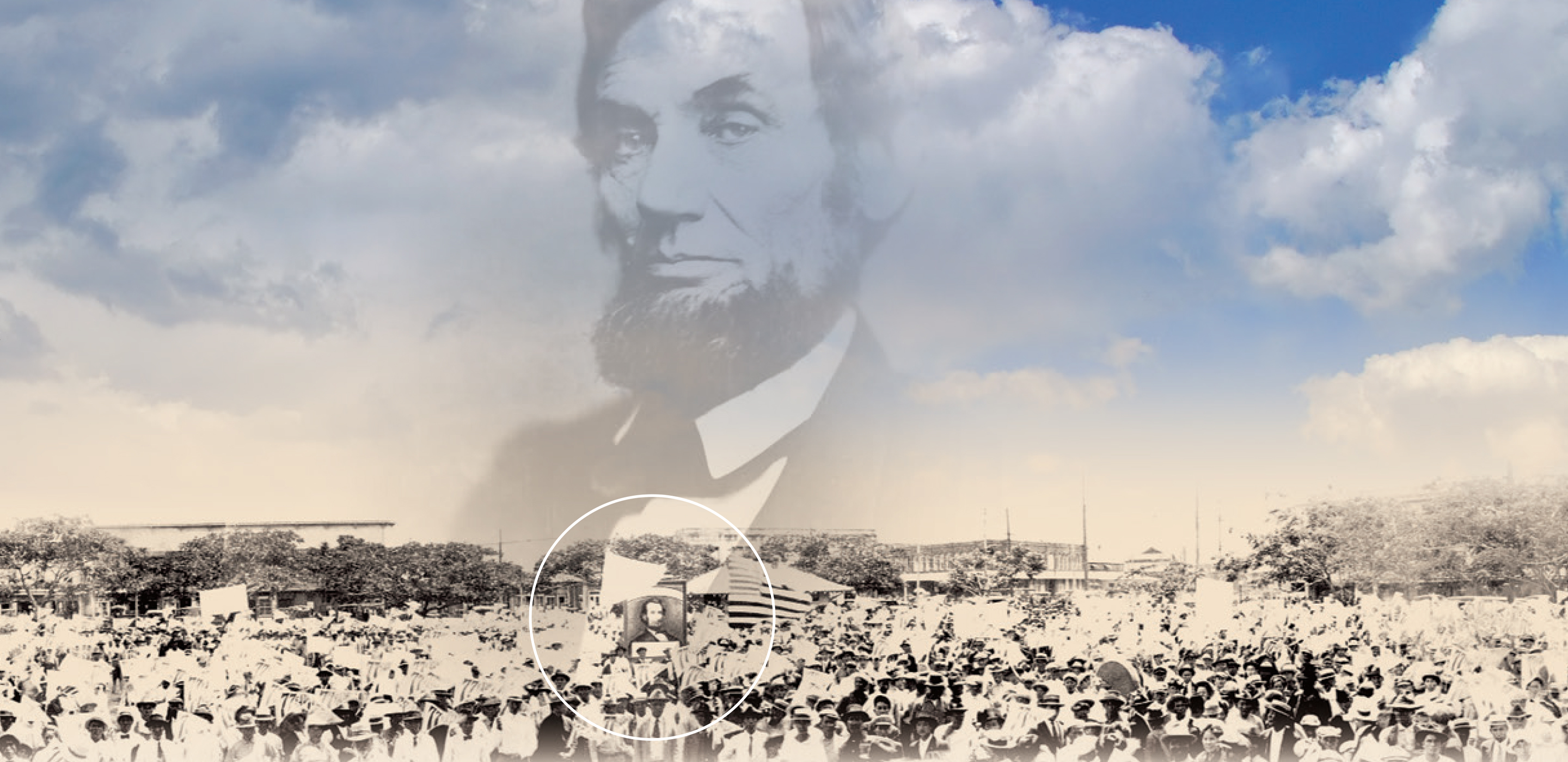

Sugar Plantation Strikes on Oahu

During the 1909 sugar plantation strike on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, Japanese strikers opposed racial and wage inequalities. This was one of many farmers’ workers strikes of this era, but we highlight this one as these workers invoked the 15th Amendment in their call for equality: “Is it not a matter of simple justice, and moral duty to give [the] same wages and same treatment to laborers of equal efficiency, irrespective of race, color, creed, nationality, or previous condition of servitude?” 3

The 15th Amendment states: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” While this strike was unrelated to voting, the inspiration from the language of equality – of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude” – is clearly drawn.

We also see the Civil War and Lincoln’s effect on the 1920 sugar strike, 11 years later. Filipino and Japanese men, women and children marched in downtown Honolulu, carrying portraits of President Abraham Lincoln, who was a symbol of liberation.

Gong Lum v. Rice (1927)

In another education case, in 1926, the nine-year-old Martha Lum tried to enroll in a white school in Bolivar County, Mississippi – but was not allowed, and informed by the superintendent that she was not white and had to enroll in the colored school. Gong Lum, Martha’s father, decided to fight for his daughter’s education, as he recognized that the white school had more advantages than the colored school.

In this case, the U.S. Supreme Court decided unanimously against Lum. Chief Justice William Howard Taft wrote racial segregation fell within the powers of the state in that, since Plessy, separate facilities and treatment fulfilled the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

Looking Towards the Future

Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, a series of immigration laws overturned Exclusion and afforded the right to naturalize. By 1954, Asians and African Americans overturned the doctrine of “separate but equal” established by Plessy through Brown v. Board of Education. The Civil Rights Act of 1966 officially affirmed the end of institutional racial segregation and legal inequality. The fight for representation, visibility, power and equality doesn’t stop, but we celebrate the history of attaining civil rights that were fought and that continue to get their due in history today.

Citations:

- Okihiro, Gary Y. “From Civil War to Civil Rights.” Asians and PI and the Civil War, edited by Carol Shively, National Park Service, Washington, District of Columbia, 2014, p. 212, Accessed 15 May 2024.

- Okihiro, Gary Y. “From Civil War to Civil Rights.” Asians and PI and the Civil War, edited by Carol Shively, National Park Service, Washington, District of Columbia, 2014, pp. 215, Accessed 15 May 2024.

- The House Joint Resolution Proposing the 14th Amendment to the Constitution, June 16, 1866; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789-1999; General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives.

- Okihiro, Gary Y. “From Civil War to Civil Rights.” Asians and PI and the Civil War, edited by Carol Shively, National Park Service, Washington, District of Columbia, 2014, pp. 216, Accessed 15 May 2024.

- The House Joint Resolution Proposing the 15th Amendment to the Constitution, December 7, 1868; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789-1999; General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives.

- Okihiro, Gary Y. “From Civil War to Civil Rights.” Asians and PI and the Civil War, edited by Carol Shively, National Park Service, Washington, District of Columbia, 2014, pp. 210–227, Accessed 15 May 2024.

Daniella Ignacio is the Communications Manager at Ford’s Theatre. She is obsessed with Asians and Pacific Islanders and the Civil War and wants you to be too.